Deconstructing JP Morgan's "Institutional DeFi" Forex Transaction: A Case Study

JPMC performed what they call an "institutional defi" transaction a few months ago. Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what it could mean for capital markets going forward.

By Vertalo Team

It feels like every week there’s a new headline that’s vying for our attention and analysis. Whether it’s BlackRock’s Larry Fink touting asset tokenization as a the ‘next generation of markets’, or perhaps State Street’s bullish statements about the ‘significant opportunity’ in asset tokenization, or finally BYN Mellon’s CEO’s comments on the necessity of BNY Mellon being involved with digital assets, large financial institutions are taking notice, gathering market intel, building products, and laying the groundwork for a blockchain-based capital markets infrastructure.

One such player is JP Morgan Chase, specifically their blockchain unit, Onyx, that made some incredible waves a few months ago with the announcement of the forex trade they had successfully completed.

We remember seeing these headlines and taking interest in what they were building, and after seeing additional headlines resurface last week based on a report authored by Oliver Wyman & JP Morgan, we broke down what information we could find that was publicly available to make sure our understanding was as complete as it could be for precisely what they did.

Full disclosure, we were only able to use public information (we would love to interview one of their team members about this more in-depth!) so there may very well be gaps between our understanding and the reality of what occurred, but to the best of our journalistic ability, based on the information, interviews, and comments from the Onyx team that we could find, here is our analysis of their “institutional defi” forex transaction.

Public blockchain, permissioned pool & protocol

Onyx’s division head, Tyrone Lobban, made a number of telling comments in interviews and podcasts after the transaction had been completed about how JPMC should approach the blockchain infrastructure world, and we were impressed by his clean articulation of the challenges facing large financial institutions and how JPMC might approach solving those specific problems.

Private blockchains are extremely difficult to get off the ground from an adoption perspective, they require ongoing maintenance from participants, and are highly subject to centralization, effectively negating the core concepts of decentralization & transparency. Nearly every attempt that we’ve seen with blockchains that promise “enterprise” or “institutional-grade” features has failed. Beyond that, private blockchains, effectively just private databases, are subject to the same security risks that face all tech-enabled companies when using typical cloud database infrastructure.

A note on private permissioned blockchains: In the eyes of the law, private permissioned blockchains are basically synonymous with private databases, which have been permissible for securities transactions for many decades, especially after the DTCC’s launch of the Direct Registration System in 2006 which made ‘digital databases’ widely usable by capital markets participants, particularly brokers, transfer agents, and stock exchanges.

We disagree with the private permissioned blockchain approach since it feels two-faced to us and leaves market players open to fraud. On the one hand, you’re seeking to instantly establish trust & credibility, by simply using the word ‘blockchain’, but on the other, it’s a fully controlled environment where the blockchain architect has complete control over everything written and recorded. Our concern in using private permissioned blockchains is that it would be technically easy for a fraudulent player to roll back the entire chain of transactions in order to remove a transaction, either legitimately or illegitimately.

There is a world of difference between remediating a transaction, through a clawback mechanism that maintains the history of the initial erroneous activity but corrects the error, and unwinding the entire blockchain to completely erase a transaction and its associated history. For this reason, we are a believer that private permissioned blockchains will not have the hold that the public permissionless blockchains do, since the public permissionless chains should always maintain the historicity and immutability of the ledger, barring any cataclysmic meltdown or operational ceasefire. We see no reason why large financial institutions can’t use public blockchains with private permissioned protocols, reaping the benefits of a controlled environment, without the risks of fraud where the historicity and immutability of the data is concerned.

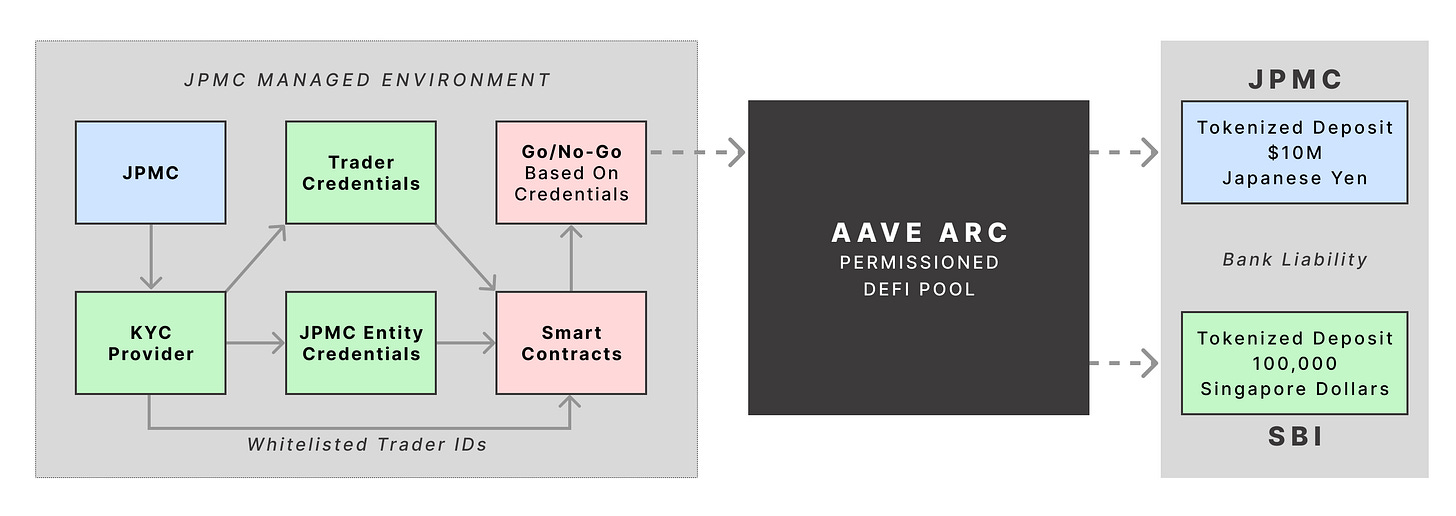

Onyx performed this transaction on Polygon, an EVM-compatible sidechain, to keep transaction fees minimal and latency time low, but beyond that, the environment they constructed was a permissioned one, allowing only whitelisted traders access and permission into the transaction and protocol itself. Put another way, rather than use a private blockchain, Onyx chose to use a public blockchain, but a private permissioned protocol, with onchain identity and other controls in place to make the transaction possible and compliant. See Aave Arc, the permissioned protocol that they used, to learn more about the combination of public blockchains & private permissioned protocols.

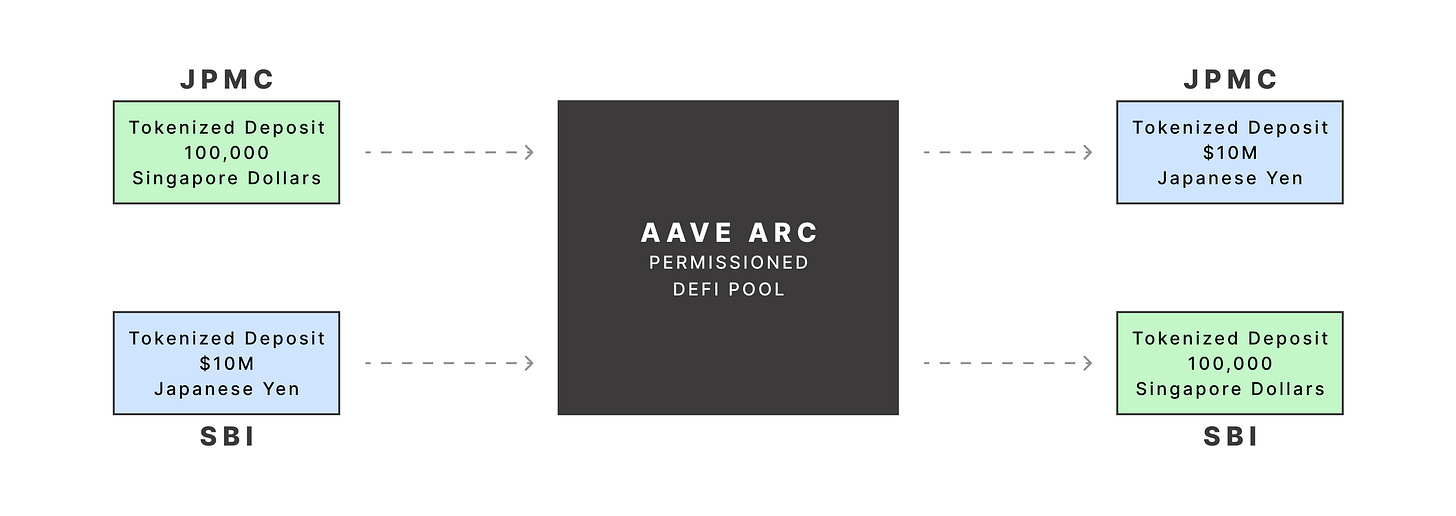

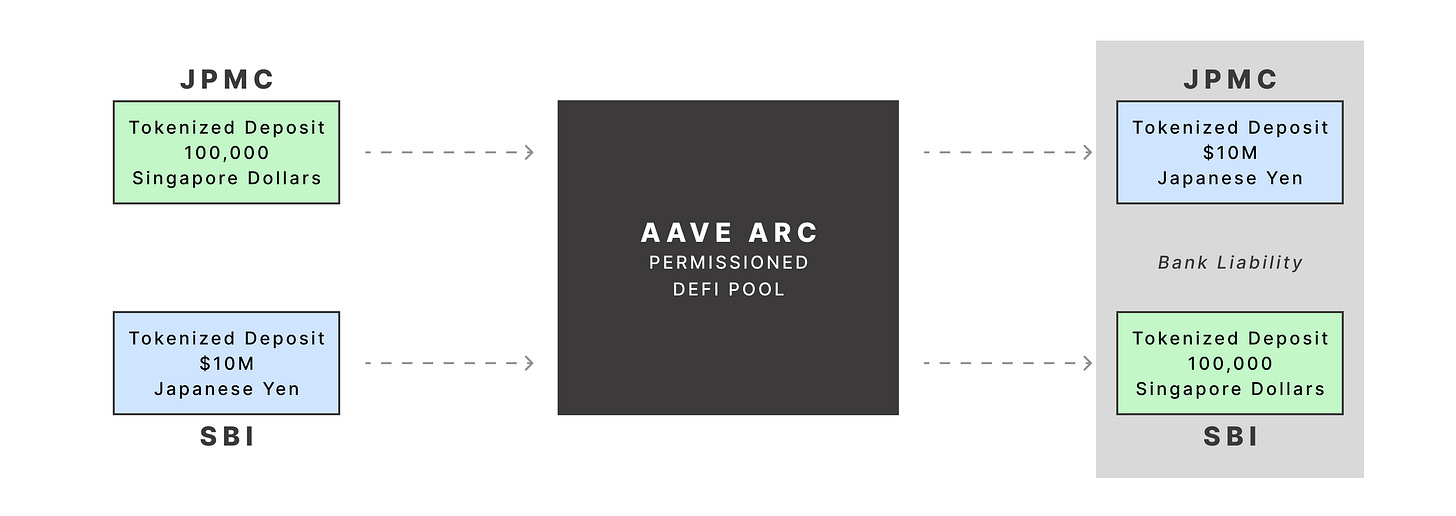

At its core, this was a simple foreign exchange transaction, whereby two parties held currencies of different denominations, and pledged one for the other through the Aave Arc protocol. The important differences to note between this transaction and a standard forex transaction are as follow:

First and foremost, Aave is a borrowing and lending protocol, not a decentralized exchange. This means that SBI & JPMC respectively had pledged their asset (the tokenized currency deposits) and received the other’s asset in exchange. In the defi world, you typically pledge your asset, say ETH, and in turn you receive a liquidity pool (LP) token, providing the holder with yield as long as they maintain ownership of the LP token by keeping their pledged asset (ETH) inside the pool for lending purposes. This was the same, except that instead of ETH & an LP token, it was tokenized Japanese Yen & tokenized Singapore Dollars.

Next, Aave is not a forex support protocol where fiat is concerned. They are a decentralized lending platform and open-source liquidity protocol for digital assets and cryptocurrencies. As far as we know, Aave is not a money transmitter nor do they have any method for moving fiat from one institution to the next, which makes this transaction a monumental leap in terms of using their technology to create an entirely new market, compliantly.

Because of the fiat restrictions that Aave is unable to work around, JPMC’s transaction was that of tokenized deposits rather than stablecoins or fiat itself. This distinction, while subtle, is absolutely critical as other capital markets players such as Figure take a similar approach to executing transactions on-chain, whereby the tokenized instrument functions as a liability of the bank, rather than a stablecoin like USDC that is vaulted and backed by paper fiat in a custodial bank.

See this solid high-level breakdown of forex transactions with graphics from IG if you’d like to dig in more.

Rather than trading between GBP & USD, the pair was tokenized Singaporean Dollars & tokenized Japanese Yen.

Tokenized Currency vs. Stablecoins

While at the Digital Assets At Duke event last month, Rob Morgan, the CEO of the USDF Consortium made several statements that felt in line with Onyx’s position, especially about the management and full backing of stablecoins vs. the flexibility of tokenized deposits that can function as bank liabilities and support credit creation.

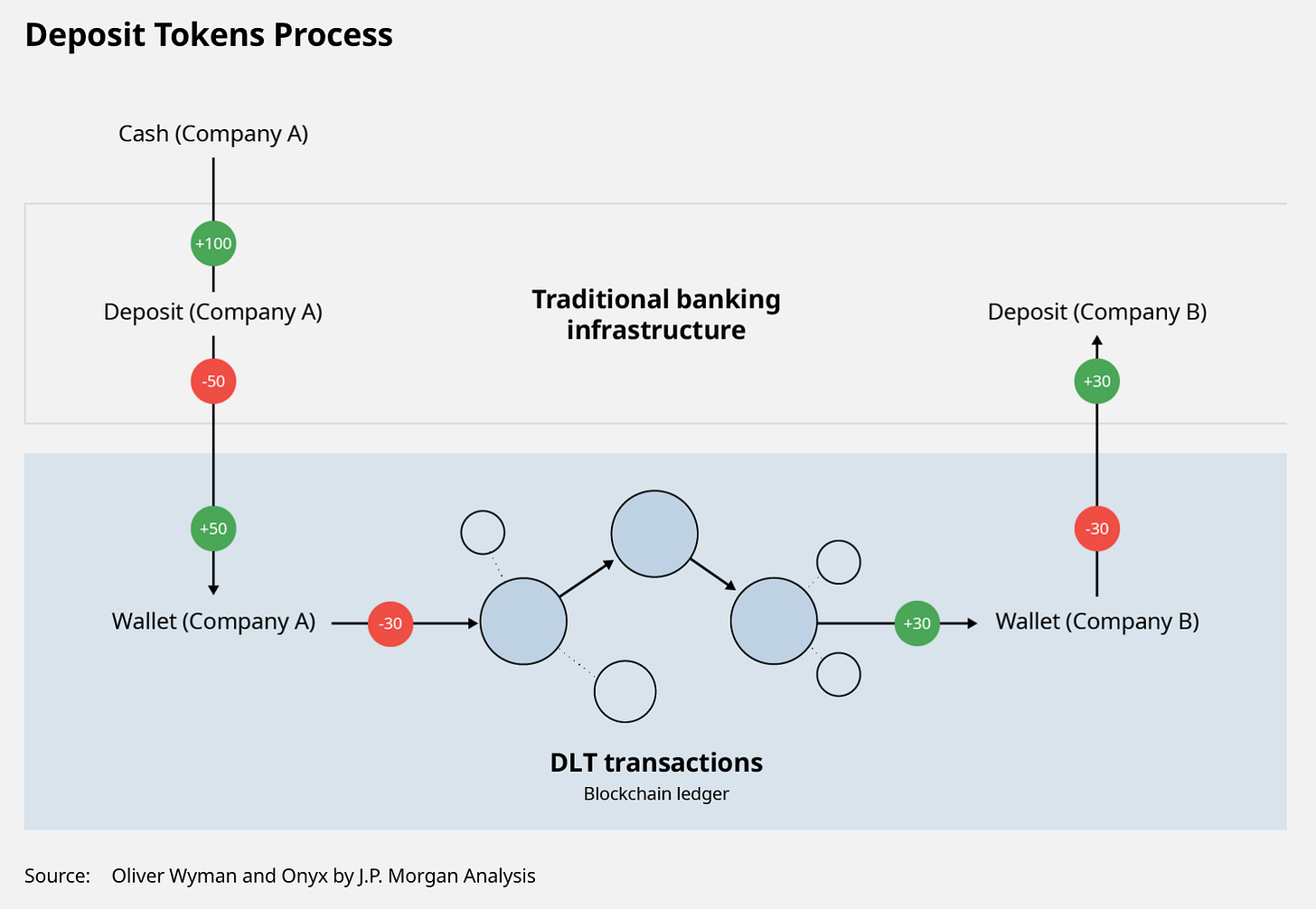

This strikes at the heart of fractional reserve banking, the flaws of which we’ll set aside entirely for this analysis, but instead we wish to highlight that with a traditional stablecoin like USDC, for every USDC coin in circulation, there must be a 1:1 backing of actual US Dollars in an audited bank vault, whereas with tokenized deposits, banks can create credit as liabilities of the bank on top of the asset of the depositor. This difference between tokenized deposits and stablecoins is also the primary method many of these proprietary payment systems, like JPM Coin, Figure, or Signature Bank, are able to run transactions 24/7, rather than being bound by the traditional hours of the modern banking system.

Just last week (as of this writing), Oliver Wyman and Onyx released a research report into the value of tokenized deposits as a method for facilitating immediate or instantaneous transactions, intraday settlement, and collateralization.

From this diagram we learn about JPMC’s approach to building blockchain in concert with existing banking infrastructure, rather than seeking to replace it lock, stock, and barrel. We’ve said it before and will repeat it here: we believe that the future of capital markets will be a hybrid combination of onchain/offchain systems that allows for faster settlement but maintain existing fiat and compliance rails.

See the full Oliver Wyman / Onyx report here.

Disclaimer: We are not attorneys, broker-dealers, investment advisors, or wealth advisors. Nothing presented herein is nor should it be considered as legal, professional, business, investment, or any other kind of advice. The information presented here is done so for educational, informational, and entertainment purposes only. Always consult a licensed professional before taking professional, investment, or legal action.

Transaction Flow

Since Aave is a lending protocol, these tokenized deposits were deposited with the express purpose of being borrowed by a whitelisted & approved counterparty, with SBI providing the collateral of tokenized yen, and Onyx providing the collateral of tokenized Singapore dollars.

The basic flow can be broken down as follows:

Remember, the tokenized deposit is a liability of the bank. In a podcast detailing the transaction, Lobban called tokenized deposits “effectively debt instruments,” but ones that can act to maintain the liquidity of the modern banking system, unlike a reserve-backed stablecoin, which typically must be backed based on a reserve mandate from the stablecoin issuer themselves. This requisite reserve backing can make both credit creation difficult and cause liquidity problems for the system as a whole, something Lobban also mentioned in several interviews after the transaction was completed.

With that in mind, here’s the visual again:

This was the general idea for the transaction - using Aave, which is not a forex provider, to support the borrowing and lending of assets from two counterparties between one another. It went through the Aave protocol, pledged and borrowed by both parties, and was not settled bilaterally, although that could certainly be enabled with a decentralized exchange like Uniswap.

Onchain ID Management

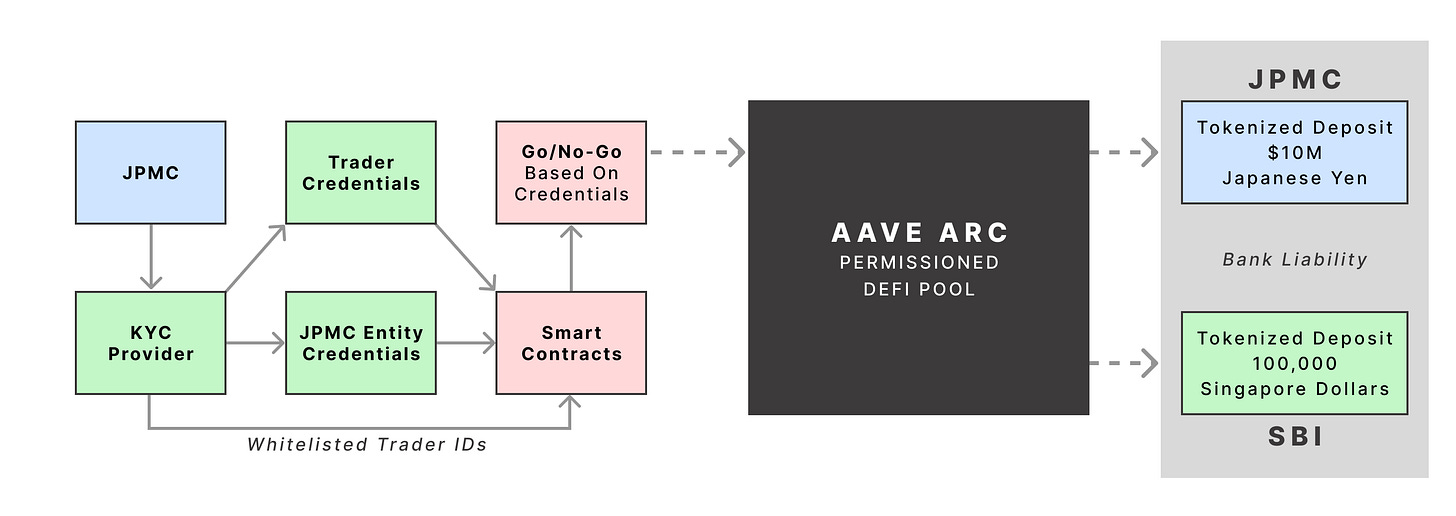

In order to properly facilitate this transaction, a system for associating the identity of these wallets on chain had to be constructed. Remember, most public blockchains that support asset tokenization are pseudonymous, not anonymous, meaning that with proper infrastructure and tooling, you can confirm and maintain the identity of the owner of a wallet. In order to execute this transaction, Onyx split the credentials into two components, both of which were needed to proceed:

ID of the entity (e.g. Vertalo)

ID of the individual trader (e.g. Collin Sellers)

Onyx enlisted the support of identity credentials, called “Verifiable Credentials” to manage both the identity of the entity, as well as individual trader’s identity. Lobban mentioned in multiple instances how this part of what they built was something they were very proud of.

The ID product is also intriguing because the permissions of it were supposedly designed to be managed at the user level, not by a government or central entity. Specifically, it was noted that Onyx:

Does not write personally identifiable information (PII) on chain, and

They only allow “programmability” of the ID to be set by the end user, preventing the weaponization of the tech against end users

This attention to detail was something that really caught our attention, since onchain identity will be an important factor in blockchain-based capital markets, but this can also represent a danger to privacy, property rights, and the freedom to transact should it be weaponized against you, especially extrajudicially.

We were very glad to hear Onyx was highly aware of this and had worked to incorporate controls into their systems to prevent the identity technology being used against traders, corporate entities, or others. The United States has led global capital markets for centuries precisely because of stable and dependable property rights for individuals, corporations, even governments, both domestic and international, and we believe it is essential we keep that top of mind as we build new markets with emerging technologies like big data, blockchain, and artificial intelligence.

Public protocol, permissioned access

One thing we heard repeatedly from the Onyx team in was that they were insistent that they not require Aave to modify their existing smart contracts and pooling protocols, but rather that Onyx feed into Aave’s universe as it stands, only applying changes outside the protocol where JPMC felt it necessary. This hybrid approach is one we expect to see a lot more of from large financial institutions going forward.

With regulatory constraints in mind, here’s what the flow looked like broken down into steps:

But again, let’s remember that everything preceding Aave was managed entirely by Onyx in support of compliance, banking standards, and their own internal requirements, which means that it effectively looked like this:

This was executed on a public blockchain, through a private permissioned pool, with private permissioned protocols, in support of a currency-for-currency forex transaction using tokenized deposits as bank liabilities. Pretty phenomenal.

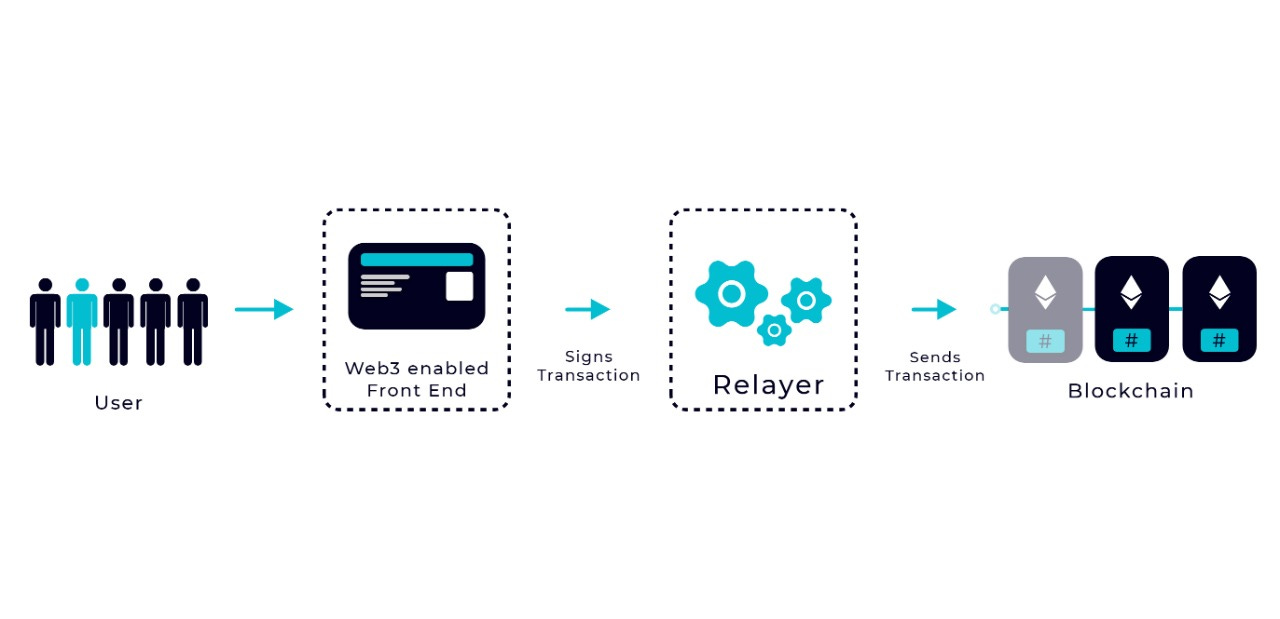

Gasless Transaction

The final thing to note here was around using gas to pay for the transaction itself. Because of Basel III restrictions, as well as internal standards around custody and compliance, JPMC as a bank can’t hold or custody crypto*, which presents as a challenge when paying the Polygon network gas for the cost of the transaction; in this case the transaction cost ~$18 to execute.

*strictly speaking, it’s not that banks under BIS supervision *can’t* hold crypto, but rather that up until Dec. ‘22 the risk weighting of holding crypto in bank custody was 1250%, making crypto extremely heavy and difficult to work with from a balance-sheet management perspective. That and JP Morgan Chase’s CEO Jamie Dimon has not been shy with his disdain for the crypto industry as a whole, so it’s no surprise that JPMC as an institution would opt against holding crypto (for now).

In order to satisfy their situational need, Onyx employed a company called Biconomy who has this notion of “Gasless Transactions” that allow JPMC to fill a wallet, but not maintain custody over it, whose express purpose was for gas consumption, and then write permissions onchain as to who can dip into that wallet when paying the network for a transaction. This is also referred to as a “meta transaction”, which are widely available and used across the defi space in a myriad of cases. From Biconomy we see the definition of a meta transaction to make a transaction “gasless”:

How do Gasless Transactions Work?

Sending a meta-transaction is similar to sending a standard transaction (from, to, value ... and signature) except that instead of sending it directly to the Blockchain, it sends the meta-transaction to a third party who will take care of the gas.

The Relayer, who is not Onyx but an independent third party, is responsible for vaulting the crypto and handling the costs of the gas, then relaying the transaction to the blockchain. For dealing with how rigorous JPMC’s compliance standards are, using Meta Transactions to achieve “gaslessness” is both simple & brilliant.

We expect to see other banking institutions setting up symbiotic relationships with gas providers or digital asset custodians to support smart-contract permissioned transactions like this in the future.

Conclusion

Onyx’s “institutional defi” transaction was pretty unique in terms of a large-scale financial institution executing a defi permissioned transaction onchain. The process included:

Public blockchain

Permissioned protocols

Permissioned liquidity pool, Aave Arc

…as well as wholly managed components for compliance, including:

On-chain identity, for both entity & trader

Gasless (meta) transactions

Tokenized bank deposits (not stablecoins)

Forex transaction utilizing a borrowing & lending protocol

As we see more and more institutions build products around and with blockchain, we expect to see other players employing a similar approach, and hope they can learn from this process and apply the lessons of those who’ve done the work, understand the rubber-meets-the-road nuances, and have successfully built on top of blockchain and with decentralized applications.

Till next time.

Interested in connecting over the digital asset ecosystem, capital markets, or blockchain-based securities? Reach out to us on LinkedIn or Twitter!

Sources

JPMorgan Trade on Public Blockchain ‘Monumental Step’ for DeFi

‘Deposit Tokens’ Could Trade On DeFi Like Stablecoins: JPMorgan

JP Morgan Sees Advantages in Deposit Tokens Over Stablecoins for Commercial Bank Blockchains

Report: Institutional DeFi: The Next Generation of Finance?

Onyx’s Tyrone Lobban Takes Us Behind the Scenes of JP Morgan’s First DeFi Trade (The Defiant Podcast, Nov. 18 2022)

Thanks for this in-depth study. Really comprehensive.

Here are two more observations from my side

In Project Guardian, they were two borrowing transactions rather than a FX trade (PvP). It was not made atomically at transaction level (one ethereum transaction to complete the swap). Certain coordination including the fixed rate (1 SGD = 104.02941 YEN per the transactions recorded in Polygon) needed to be agreed and possibly done off-chain.

While Project Guardian adopted VC for identity, recently there was another project (Project DAMA) that Deutsche Bank was using a SBT (soul-bound token), a modified ERC-721 NFT where transferability was removed. In order to make this work, a modified DEX was needed to check the SBT before it proceeded the normal DEX process. Using the ERC-based token has advantages over using VC, as it can leverage metamask to handle the token. For Project Guardian, a modified wallet was needed to incorporate the credentials, and the transaction was not natively an Aave arc transaction at all.