SEC vs. LBRY: Will this define crypto, or is it just another ruling?

The ruling handed down on Nov. 7 2022 has interesting implications. Let's break them down together and consider the questions it raises.

By Vertalo Team

While the rest of the world is focused on the drama between Binance, FTX, and Sam Bankman-Fried and their now-defunct merger, some news came out that we believe will have more material impact and meaning for the entire crypto market. Let’s break down exactly what happened, what the judgement highlights, who this might impact, and what implications it has on the market going forward.

If you’d like to read the full report yourselves as we go through the points made, you can find it here: SEC vs. LBRY Ruling.

Please note, this represents our (admittedly) limited understanding of our judicial system, We are not lawyers nor do we claim to be experts in legal proceedings. Our purpose in this piece is to highlight the potential impact this case could serve if this stands to establish precedent and influence future rulings within the crypto space. The reality for us is that the ruling raises more questions than it does provide answers, due to the nature of the ruling.

Binding vs. Persuasive Authority

Before we begin, an important note on this ruling and the types of rulings that come to influence our legal system and establish precedent for future rulings. Broadly speaking, rulings like the one at hand fall under two categories of classification:

Binding Authority

Persuasive Authority

Binding Authority, also referred to as mandatory authority, refers to cases, statutes, or regulations that a court must follow because they bind the court. Persuasive authority refers to cases, statutes, or regulations that the court may follow but does not have to follow.

The SEC vs. LBRY judgement falls under Persuasive Authority, and is therefore not wholly binding for future rulings. The question that comes to mind comes down to timing. We are skeptical that this case will have nothing to do with future cases, especially the ongoing SEC vs. Ripple Labs case. While we don’t have hard evidence to support this, we must ask if the SEC’s apparent stonewalling and dragging of their feet didn’t have something to do with this case against LBRY, specifically the timing thereof, and its subsequent ruling. Should future courts look to this case as firm precedent, it could mean much more influence and control over crypto markets overall for the SEC, a position that Commissioner Gensler has not been shy about.

That said, this case was not one of mandatory ruling, this was not a congressional law nor was it fully binding in the eyes of the federal government.

Additionally, the LBRY case was heard in the U.S. First District, which means the LBRY decision does not necessarily have a direct impact on the SEC v. Ripple case currently being heard in the Second District. Many, myself included, believe the SEC will refer to the LBRY decision in its Ripple arguments despite this difference.

With that clearly stated, we can dig into the case more fully.

Disclaimer: We are not attorneys, broker-dealers, investment advisors, or wealth advisors. Nothing presented herein is nor should it be considered as legal, professional, business, investment, or any other kind of advice. The information presented herein is done so for educational, informational, and entertainment purposes only. Always consult a licensed professional before taking professional, investment, or legal action.

Let’s set the stage.

LBRY is a decentralized file storage company, similar to Filecoin, Zilliqa, Storj, Theta, among many others, who’s mission was to create a platform and ecosystem that decentralizes ownership, returning power to content creators a la publishing and ownership rights. Their website bears the headline, “LBRY does to publishing, what Bitcoin did to money.”

Bold claim, we’ll give them that.

LBRY performed an initial coin offering, the famed “ICO” as it has been come to be known, in June of 2016, which the summary judgement references. The core question on the table was whether or not the LBC “credits”, bearer asset tokens, were securities? Before we dig in, here are some additional elements that are important in this ruling.

LBRY created 1 Billion LBC tokens, with the following distribution schedule:

According to CoinMarketCap however, the total supply of LBC tokens currently stands at 1,083,202,000. Where the additional 83M coins came from is not clear.

The pre-mine split meant that 40% of the total initial supply of LBC tokens were maintained by LBRY as an entity. This is extremely important, since one of the main points the SEC makes has to do with the tokens being pre-mined themselves. Also note, LBRY raised capital from angel investors, obtained $500K in debt financing, including offering 2M LBC credits as part of the exchange for the debt financing, and used roughly 142 million LBC tokens as payment “to incentivize users, software developers, and software testers, as well as compensate employees and contractors.”

At the time of the lawsuit being filed, they note that roughly half of the 100 million units set aside for the operational fund had been expended.

Now, the ruling is clear that LBRY is not contending that they sold LBC tokens, including a pre-mine and schedule set out above, only that LBC tokens are not securities, nor were they given fair notice that they needed to register the offering, or an exemption, with the SEC. In concluding that LBC tokens are securities, they contend that no fair notice is needed since the laws for securities registrations and exemptions are and have existed for many years.

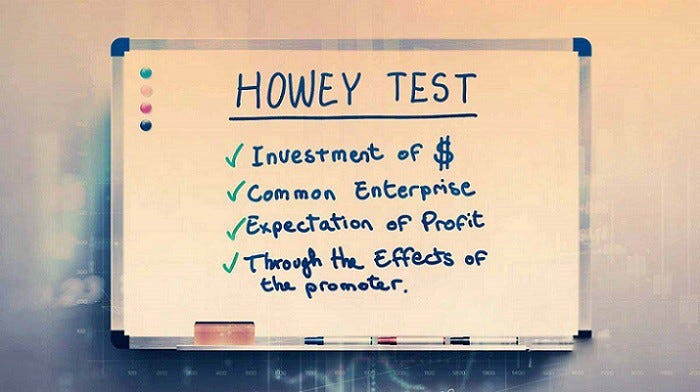

The Howey Test

The judgement cites the Howey Test, the famous case from 1946 that brought us the formal definition of a security. Per the Howey Test, there are four elements up for consideration when looking at an offering to determine whether it is an investment contract, and therefore subject to securities laws:

An investment of money

In a common enterprise

With the expectation of profits

Where the profits are derived from the efforts of the promoter (the common enterprise mentioned) or a third party

Regarding LBRY and their LBC token:

Did an investment of money occur? Yes. Money changed hands when investors purchased LBC tokens.

In a common enterprise? Yes. LBRY, an incorporated company, is the central issuing entity behind the LBC tokens and LBRY blockchain.

With those points clearly satisfied, the SEC moves on to three & four: the expectation of profits, derived from the efforts of the promoter.

The basis for the SEC’s lawsuit: why was this a securities offering?

“The focus of the inquiry is on the objective economic realities of the transaction rather than the form that the transaction takes.” (pg 7)

“Thus, the issue to be decided is whether the economic realities surrounding LBRY’s offerings of LBC led investors to have “a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.” (pg 8)

Here the SEC is being very clear that the nature of the transaction is not what matters to them (eg a blockchain-based ICO for tokens vs. plain-Jane fiat changing hands), but that the issue on the table is whether investors had an expectation of profits derived from the efforts of LBRY.

Now, the first point being made by the judgement is that LBRY, on a number of occasions, tout the potential value that these tokens could hold should they succeed in making LBRY a successful and widely used product. They cite emails and other forms of communication as the basis of this point. Some of the highlights include:

“What LBRY did claim to know though was “that the long-term value proposition of LBRY is tremendous, but also dependent on our team staying focused on the task at hand: building this thing.” It then closed the post by announcing a policy of neutrality with respect to LBC's price but plainly stating that “[o]ver the long-term, the interests of LBRY and the holders of [LBC] are aligned.””(pg 10)

Further, LBRY COO Josh Finer made the following comments that are included in the memorandum:

“In August 2016, the COO of LBRY, Josh Finer, emailed a potential investor explaining that the company was “currently negotiating private placements of LBC with several [other] investors” and asked the recipient to write him back “if there is interest” so the two could “chat.” The thrust of the email (subject line: “LBRY Credits Now Trading – LBC”) is clear.

He called it a “private placement”. It doesn’t get more clear that this was an investment, both to him as an operator and director of LBRY, as well as to the investor.

After briefly noting that the platform was up and running, the COO explained how LBC are being traded on “major crypto exchanges” and that trading volume is moving at a healthy clip. The “opportunity is obvious,” wrote the COO, “buy a bunch of credits, put them away safely, and hope that in 1-3 years we’ve appreciated even 10% of how much Bitcoin has in the past few years.” He wraps up by pitching LBRY’s commitment to building its Network: “[i]f our product has the utility we plan, the credits should appreciate accordingly.”” (pgs 10-11)

If the recent cases against Kim Kardashian and Floyd Mayweather have taught us anything, it’s that the promotion of instruments that look like investment contracts is not something that can be done lightly. There’s a reason registered investment advisors on CNBC don’t recommend buying equities; it’s not a buy recommendation, it’s that they “like the stock.” Now, most of us recognize this for what it is, but still, the wording around investment instruments is and will continue to be something that is highly scrutinized. Another example - those who engage in Investor Relations for public companies undergo months of full-time training to prevent insider trading or improper disclosures.

According to the SEC, “LBRY has - at key moments and despite its protestations - been acutely aware of LBC’s potential value as an investment. And it made sure potential investors were too.” (pg. 9)

Aligned Incentives

In January 2018, LBRY’s CEO penned a public article citing how blockchain tokens can be used to align incentives.

“Because a blockchain token ‘has value in proportion to the usage and success of the network,’ developers are incentivized to work to develop and promote new uses for blockchain. As Kauffman put it:

“It means that the people who discover and utilize a new protocol or network when it’s just getting off the ground can reap substantial value by being there first. This solves the incentive problems around being a first-mover and softens the pain of using a service that probably won’t be as feature-rich or slick as established competitors’ options. It provides a source of funding for the development of the protocol. The creators can use the token to pay for the salaries and equipment required to get it started.” (pg 13)

We’ll reiterate that punch line - “it provides a source of funding for the development of the protocol.”

So does raising capital via equity fundraising.

Between the pre-mine and comments from the operators, LBC tokens sure look like an equity investment in a startup. One of the most attractive reasons selling equity to angel and venture investors has been a primary funding method for startups, is exactly what this case cites - the incentives are properly aligned. If the company does right by the market, their customers, and their investors, everyone should win as product-market fit is achieved and the value of the equity increases. It’s this alignment that the SEC has really honed in on.

The SEC continues, describing the nature of the statements made publicly about LBC tokens with this, “These statements are representative of LBRY’s overall messaging about the growth potential for LBC, and thus the SEC is correct that potential investors would understand that LBRY was pitching a speculative value proposition for its digital token. LBRY’s messaging amounts to precisely the “not-very-subtle form of economic inducement” the First Circuit identified in SG as evidencing Howey’s “expectation of profits.”” (pg 14)

Further, the SEC clarifies that “a disclaimer cannot undo the objective economic realities of a transaction.” As much as those of us who operate in this space would like it to, this feels to us as though they are restating the old adage, “If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and acts like a duck, it’s probably, in fact, a duck.”

“LBRY made no secret in its communications with potential investors that it expected LBC to grow in value through its managerial and entrepreneurial efforts. But even if it had never explicitly broadcast its views on the subject, any reasonable investor who was familiar with the company’s business model would have understood the connection.” (pg 15)

Bold of this judge to assume crypto traders are reasonable, but that’s not what’s up for debate.

Social Media Mentions

One final thing to note regarding public comments about LBC tokens as potential investment instruments, this case cites both Reddit & Twitter posts. We can’t access the referenced Tweets or Reddit posts (damn paywall) but we can assume the posts referenced price action, price increase, or some other potential where the price per token was concerned. While there are many forums online for discussing price action, stocks, bonds, and other financial products, the online mentions here seem particularly important in emphasizing and furthering the idea that LBC tokens were an investment product, and that the market at large considered them as such.

(“[W]hile the subjective intent of the purchasers may have some bearing on the issue of whether they entered into investment contracts, we must focus our inquiry on what the purchasers were offered or promised.”). pg. 18

We must also wonder if LBRY’s lack of refutation against these online comments, bolstered by the fact that their chief officers were talking about these as having the potential for investment, was a factor in the SEC’s position.

Implications for Crypto Companies

The obvious implication here is that other cryptocurrencies whose issuers fulfill both criterion set out by the SEC (pre-mine and/or pre-issuance of some sort to the controlling entity which meant incentives were aligned + comments that make token purchases look like investments) could be found guilty of conducting unregistered securities offerings.

While we don’t have access to private communications for the operators of the following companies, here are some of the largest cryptocurrencies with centralized entities behind them who conducted ICO’s that included large percentages of the total supply of coins being pre or instantly mined:

Ethereum

XRP

Solana

Avalanche

Binance

Chainlink

Cardano

Polkadot

Algorand

Cronos

Hedera

Tron

Stellar

Conversely, here are some of the largest and most well-known cryptocurrencies, that were not pre-mined or pre-issued in some way:

Bitcoin*

Litecoin**

Monero

Doge

Shiba

*Bitcoin had no pre-mine or angel investors but Satoshi Nakamoto was the first miner on the network, meaning that they ended up with a large swath (nearly 1M BTC) for themselves. We exclude Bitcoin here because in order for the Bitcoin network to launch there had to be early adopters handling the mining, which meant that some of those early adopters were able to pick up large amounts of BTC at practically no expense. Today, Bitcoin is sufficiently decentralized in a global manner such that even the SEC is comfortable stating that Bitcoin looks more like a commodity than a security.

**Litecoin came with a 150 LTC pre-mine for the genesis block of that blockchain, but with a total supply of 84 Million, We’re also comfortable excluding Litecoin as a crypto that was pre-mined since it was a functional requirement to kickstart their chain.

A quick aside, on a macro level, the primary focus for regulators seems to come down the nature of a fluctuating price against the US dollar. One example we often refer to is World of Warcraft, which sells gold coins as in-game currency for purchases of armor or other utilities as players need them. Billions of dollars have been processed through the WoW marketplace, but the SEC has never once batted an eye at Blizzard Entertainment, the creators of World of Warcraft, since the underlying USD value is and has always been, pegged and stable.

Additional Fallout

Now, if we were one of the companies who conducted ICO’s with a pre-mine, insta-mine, or pre issuance of some sort, we would be highly concerned at the criteria laid out in this case. Not only do they cite private communications between executive officers, but as noted above, they also cite online communications, include tweets on Twitter and community posts on Reddit where retail investors could have been led to believe that these instruments were investment contracts with a reasonable expectation of profit.

A quick look at r/Solana on Reddit shows 4 of the top 10 posts this year mentioning price action, specifically the word “investment”. We have no doubt we could find similar mentions or posts on r/Ethereum, r/Ripple, r/Algorand, or others. The top “hot” post on the Algorand subreddit as of this writing is the following meme about dollar cost averaging and still being down on your investment.

Investors clearly consider cryptocurrencies financial instruments, and anyone with any kind of access to social media can see that.

Disgorgement

The ruling states that investors who invested in LBC tokens would be eligible for disgorgement under the law. Disgorgement is defined as:

Disgorgement is the legally mandated repayment of ill-gotten gains imposed on wrongdoers by the courts. Funds that were received through illegal or unethical business transactions are disgorged, or paid back, often with interest and/or penalties to those affected by the action. Disgorgement is a remedial civil action, rather than punitive civil action. That means it seeks to make those harmed whole rather than to excessively punish wrong-doers.

The question this raises immediately, since the ruling does not make it explicitly clear, is whether or not this repayment would need to happen in kind or not. We would absolutely assume, as would most people, that a USD cash repayment would be expected here, especially considering that LBRY market cap is roughly $12.5M, down 99% from its all-time high when it had touched $1.2B back in July of 2016, but again, it’s not clearly stated. The question this elicits is what if a company that had issued a cryptocurrency was up from their initial issuance price? Ethereum for example, was $0.25 / coin at their ICO, and as of this writing it’s trading around $1100 USD.

A large liquidation of ETH, to return capital to those who participated in the ICO, could flood the market with ETH and cause the price to crash. What would happen to the circulating supply of remaining tokens? After all, plenty who operate in the crypto market live abroad in jurisdictions outside the SEC’s responsibility, and it certainly wouldn’t be fair to them to lose value due to a liquidation needed to pay disgorgement expenses. We have absolutely no idea how the SEC might consider this, since usually their enforcement actions come from investors being hurt, not benefitting, from illegal activity.

We’re also reminded of the infamous Mt. Gox collapse and subsequent lawsuits. Mt. Gox was ordered to return capital as part of their settlement, which was initially set to be handled via USD. This was well after the price of Bitcoin had skyrocketed, and since Mt. Gox still had roughly 1/4 the total Bitcoin thought to be lost on their balance sheet, they had the ability to disperse it, but wanted to return the capital in the form of USD, which would have netted them a huge sum due to their ability to keep the remaining Bitcoin for themselves. This led to a number of lawsuits, including a class action suit which was ultimately rejected last year.

Implications for Crypto Exchanges

Will the SEC use this ruling as the basis for pursuing action against the crypto exchanges who offered this product? The selling of an unregistered security is punishable via fine from the SEC, but our questions come down to whether or not the SEC intends to pursue this action, or grandfather in those who committed these actions with a symbolic slap on the wrist.

A cursory look on FINRA’s BrokerCheck gives us an idea of fines levied against large players for simple violations. A recent one from Wells Fargo came in at $4M for the improper handling of information. Another was $1.2M to JP Morgan for improper handling of customer account around Rule 201 of Regulation S-ID, which refers to broker’s needs to verify customer account types, specifically around the “covered account” designation.

In 2019 however, we also saw the SEC bring a suit resulting in a $16 Million fine (the full amount raised plus interest) against a company called ICOBox for enabling, not conducting, unregistered securities sales.

According to the SEC’s complaint, ICOBox raised funds in 2017 to develop a platform for initial coin offerings by selling, in an unregistered offering, roughly $14.6 million of “ICOS” tokens to over 2,000 investors. The complaint alleges that defendants claimed the tokens would increase in value upon trading and that ICOS token holders would be able to swap them at a discount for other tokens promoted on the ICOBox platform. See the full SEC statement here.

If every exchange who sold LBC tokens was to be visited with similar fines, you might see enforcement action against the following exchanges, forcing them to make restitution or pay disgorgement:

Bittrex

Hotbit

CoinEx

MEXC

It’s not a large list compared to other cryptocurrencies, but what if individuals were also pursued? We’ve previously cited a fascinating example where the SEC sued individuals trying to sell securities on eBay back in 1999. Peer-to-peer transfers of securities is not legal in the United States. Would the SEC seek remediation against all those who transferred LBC tokens to others in a peer-to-peer manner?

Furthermore, what about tax, Know-Your-Customer, or Anti-Money Laundering implications? You’d never pay someone in an exchange with the deed to your home, you sell your home, then use the proceeds to pay the counterparty for whatever goods or services they’re offering.

(side note, we’re of the opinion that this is most likely why Tesla stopped accepting Bitcoin as tender for their cars, not because Musk didn’t believe in the technology, but because it’s an accounting nightmare based on how the government currently classifies Bitcoin as an asset. After all, they don’t accept coffee futures as payment for a Tesla either)

Conducting securities transactions without KYC/AML is also illegal, the enforcement and punishment of which is handled by FinCEN, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. The ironic thing about their name is that the enforcement arm of FinCEN is actually the IRS. Reminds us of the gangsters of Chicago…they can’t get you for racketeering, murder, or money laundering, so they nail you for tax evasion.

To quote Joker from the animated Batman series:

Market Implications

The United States has and continues to set the standards for capital markets globally. Our concern with this case, and with some sort of sweeping regulation like what current regulators are asking for, would be the discouragement of innovation and development here in the US, instead pushing the cutting edge development and ideation overseas.

Currently US Senators John Boozman (R, AR), Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) (who is the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs) all share the opinion that the Digital Commodities Consumer Protection Act of 2022 should be pushed through immediately, following the collapse and spectacular drama of the FTX debacle. See their statements here:

Ranking Member Boozman Statement on Digital Commodities Consumer Protection Act of 2022

Statement of Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee

We’re reminded of LIBOR as one of the world’s most important interest rates, and the fact that it exists outside the United States. We’re in full support of competition when it comes to global capital markets, please don’t misunderstand, but we must wonder here if the departure of crypto, blockchain, and decentralized finance innovations could have broad implications a la LIBOR and it’s history. The abstract from this staff report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York states:

As of 2013, LIBOR underpins more than $300 trillion of financial contracts, including swaps and futures, in addition to trillions more in variable-rate mortgage and student loans. LIBOR’s volatile behavior during the financial crisis provoked questions surrounding its credibility. Ongoing regulatory investigations have uncovered misconduct by a number of financial institutions. Policymakers across the globe now face the task of reforming LIBOR in the aftermath of the scandal and crisis.

We would much prefer that America focus on legislation that fosters stability, growth, and prosperity rather than discouraging innovation domestically due to over-regulation. How many companies refuse to operate in New York because the requirements behind the notorious Bit License are too stringent?

See also, “Kill the Bit License.” CoinDesk, Oct 19, 2021.

Consistency: the cornerstone of economic activity.

Thomas Sowell, one of our favorite authors and economists, highlights the need for consistency in his seminal book, Basic Economics. One of the most important things that market participants can do to grant stability is to maintain the consistent treatment of customers, partners, or other actors as necessary. What’s fascinating, is that the consistency within certain classes is what is most important in producing stability and allowing markets to flourish - even if it’s unfair or provides preferential treatment to some group or class of people over another.

Sowell cites the differences between white Italian or Irish immigrants and Chinese immigrants in his book. If you were Chinese, you were not treated as well as a white Italian immigrant, that is clear within history books. However, from one Chinese citizen to the next, or in other words, within the class of Chinese immigrants as a whole, the treatment was remarkably consistent, which allowed economic activity to flourish. Despite the differences in treatment of the different racial groups in colonial and post-Revolutionary War America, the consistency within groups was a driver for extensive economic growth during this period.

Now, we are categorically and utterly opposed to the mistreatment of anyone because of their race, ethnic class, skin color, religion, sexual orientation, or any other similar characteristic, we want that to be perfectly clear.

So why bring this up?

Well, one approach might be to simply grandfather in existing crypto issuers, even despite the preferential treatment of giving those who were here early a pass. Regulators could do this with an eye towards producing a simple digital asset framework for those seeking to enter the space in the future. Yes, it would mean more stringent regulation for those entering from here on out, but it would also hopefully be encouraging to those here currently, without destroying value for those who were here early. The downside to this would be that investors who have been harmed would not have recourse to recoup their losses, something we can’t imagine the SEC would be comfortable with.

Based on this, and other rulings the SEC and CFTC have imposed, we don’t think it’s realistic to hope the SEC will grandfather in existing crypto companies, we think it’s far more likely for them to enforce against bad actors where investors have been demonstrably hurt.

This case could mark the beginning of a regulatory enforcement spree against companies who meet these standards and whose investors have lost their funds without fully knowing or understanding the risks involved in buying assets like these. After all, the primary directive of the SEC is to protect investors.

Personally, we believe this case will serve as precedent in the SEC vs. Ripple Labs case, the ruling of which will then be a mandatory one and will provide the SEC with binding authority to further prosecute crypto issuers and bad actors in the space. This is all conjecture, but the timing and criteria established here raise too many questions in our mind for it be inconsequential.

Conclusion

We don’t believe the implications of this case are fully clear to anyone, our intent in sharing these thoughts was to lay out some of the questions it provoked, and consider the implications of this case should it stand as precedent for future rulings.

With regards to regulating the crypto space, and digital asset securities, there is not consensus and agreement for the best method forward, both within regulatory bodies as well as between those like the SEC, CFTC, OCC, FinCEN, or others. Concerning legislation generally, what governing body these assets fall under, how to approach regulations going forward, what sort of enforcement should be applied - the opinions of these things differ from one regulator to the next. Hester Pierce, for example, has been quite forthcoming when she has disagreed with enforcement action that has been taken by Gary Gensler or the Commission overall.

This case could come to define crypto and blockchain-based assets as a whole, or it could fall by the wayside as just another judgement against some bad actors. Indeed brokers face fines every day for compliance missteps, perhaps this case will look like those and not serve to influence future rulings. Our hope is that we can come together around the treatment of these assets and create frameworks, regulations, and enforcement action that make sense and allow innovation and markets to grow and flourish, maintaining the United States as a beacon for blockchain, crypto, digital asset securities, and emerging use cases thereof.

Till next time.

Disclaimer: We are not attorneys, broker-dealers, investment advisors, or wealth advisors. Nothing written here is nor should it be considered as legal, professional, business, investment, or any other kind of advice. The information presented herein is done so for educational, informational, and entertainment purposes only. Always consult a licensed professional before taking professional, investment, or legal action.